Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Genomic analysis suggests the common kitchen vermin spread from Europe to the world. But it wasn't originally found in Europe.

A ubiquitous household pest has unexpected origins. A cockroach that lives in human dwellings all over the world is known as the German cockroach — but it did not come from Germany originally. A study published today1 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that the creature originated in South Asia and spread globally because of its affinity for human habitats.

Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus was the first scientist to describe the cockroach — which he named Blattella germanica — in 1776 in Europe, hence the assumption about its German origins. “They did not originate from there, but they were domesticated there and then started to spread across the world,” says study co-author Qian Tang, an evolutionary biologist now at Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts.

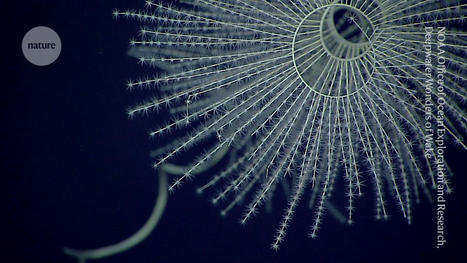

Family tree of ‘octocorals’ pushes origin of bioluminescence back to 540 million years ago, when the first animal species developed eyes.

Some 540 million years ago, an ancient group of corals developed the ability to make its own light1. Scientists have previously found that bioluminescence is an ancient trait — with one group of tiny crustaceans first making their own light an estimated 267 million years ago.

But this new finding pushes back the origins of bioluminescence even further by around 270 million years. “We had no idea it was going to be this old,” says Danielle DeLeo, an evolutionary marine biologist at Florida International University in Miami, who led the study, which was published on 24 April in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. “The fact that this trait has been retained for hundreds of millions of years really tells us that it is conferring some type of fitness advantage.”

Bioluminescence has evolved independently at least 100 times in animals and other organisms. Some glowing species, such as fireflies, use their light to communicate in the darkness. Other animals, including anglerfish, use it as a lure to attract prey, or to scare away predators. However, it’s not always clear why bioluminescence evolved. Take octocorals. These soft-bodied organisms are found in both shallow water and the deep ocean, and produce an enzyme called luciferase to break down a chemical to make light. But whether glowing octocorals use their light to attract zooplankton as prey or for some other purpose is unclear.

Interspecies competition in ancient humans saw an evolutionary trend that is the complete opposite of almost all other vertebrates.

Interspecies competition in ancient humans saw an evolutionary trend that is the complete opposite of almost all other vertebrates, according to a new study. For years, scientists assumed the main driver of the rise and fall of hominin species (which includes humans and our direct ancestors) was climate change. It is known, however, that interspecies competition is also at play as it is in most vertebrates.

New research published in Nature Ecology & Evolution examines the rate at which new species of hominin emerged over 5 million years. This speciation in our lineage, they found, is unlike almost anything else. “We have been ignoring the way competition between species has shaped our own evolutionary tree,” says lead author Dr Laura van Holstein from the University of Cambridge, UK. “The effect of climate on hominin species is only part of the story.” In most vertebrates, species evolve to fill ecological “niches.”

“The pattern we see across many early hominins is similar to all other mammals,” van Holstein says. “Speciation rates increase and then flatline, at which point extinction rates start to increase. This suggests that interspecies competition was a major evolutionary factor.”

The evidence is equivocal on whether screen time is to blame for rising levels of teen depression and anxiety — and rising hysteria could distract us from tackling the real causes.

Hundreds of researchers, myself included, have searched for the kind of large effects suggested by Haidt. Our efforts have produced a mix of no, small and mixed associations. Most data are correlative. When associations over time are found, they suggest not that social-media use predicts or causes depression, but that young people who already have mental-health problems use such platforms more often or in different ways from their healthy peers1. These are not just our data or my opinion.

Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews converge on the same message. An analysis done in 72 countries shows no consistent or measurable associations between well-being and the roll-out of social media globally6. Moreover, findings from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study, the largest long-term study of adolescent brain development in the United States, has found no evidence of drastic changes associated with digital-technology use7. Haidt, a social psychologist at New York University, is a gifted storyteller, but his tale is currently one searching for evidence.

The effect of melting polar ice could delay the need for a ‘leap second’ by three years.

An analysis1 published in Nature on 27 March has predicted that melting ice caps are slowing Earth’s rotation to such an extent that the next leap second — the mechanism used since 1972 to reconcile official time from atomic clocks with that based on Earth’s unstable speed of rotation — will be delayed by three years.

“Enough ice has melted to move sea level enough that we can actually see the rate of the Earth’s rotation has been affected,” says Duncan Agnew, a geophysicist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, and author of the study.

According to his analysis, global warming will push back the need for another leap second from 2026 to 2029. Leap seconds cause so much havoc for computing that scientists have voted to get rid of them, but not until 2035. Researchers are especially dreading the next leap second, because, for the first time, it is likely to be a negative, skipped second, rather than an extra one added in.

We found an issue with a specific type of brain imaging study and tried to share it with the field. Then the backlash began.

In 2022, we caused a stir when, together with Brenden Tervo-Clemmens and Damien Fair, we published an article in Nature titled “Reproducible brain-wide association studies require thousands of participants.” The study garnered a lot of attention—press coverage, including in Spectrum, as well as editorials and commentary in journals. In hindsight, the consternation we caused in calling for larger sample sizes makes sense; up to that point, most brain imaging studies of this type were based on samples with fewer than 100 participants, so our findings called for a major change.

But it was an eye-opening experience that taught us how difficult it is to convey a nuanced scientific message and to guard against oversimplifications and misunderstandings, even among experts. Being scientific is hard for human brains, but as an adversarial collaboration on a massive scale, science is our only method for collectively separating how we want things to be from how they are.

Magpies are expert problem-solvers – but just how good they are seems to depend on the size of the social group they grow up in.

Our study focused on Western Australian magpies, which unlike their eastern counterparts live in large, cooperative social groups all year round. We put young fledglings – and their mothers – through a test of their learning abilities.

We made wooden “puzzle boards” with holes covered by different-coloured lids. For each bird, we hid a tasty food reward under the lid of one particular colour. We also tested each bird alone, so it couldn’t copy the answer from its friends. A mother magpie and a fledgling standing side by side.

Do fledgling magpies get their smarts from their mothers? Lizzie Speechley Through trial and error, the magpies had to figure out which colour was associated with the food prize. We knew the birds had mastered the puzzle when they picked the rewarded colour in 10 out of 12 consecutive attempts. We tested fledglings at 100, 200 and 300 days after leaving the nest.

While they improved at solving the puzzle as they developed, the cognitive performance of the young magpies showed little connection to the problem-solving prowess of their mothers.

Instead, the key factor influencing how quickly the fledglings learned to pick the correct colour was the size of their social group. Birds raised in larger groups solved the test significantly faster than those growing up in smaller social groups.

The evidence is clear, write epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett: “large differences in income are a powerful social stressor that is increasingly rendering societies dysfunctional”. The solution, they argue, is for policymakers to choose progressive forms of taxation and close tax havens and loopholes. “Reducing economic inequality is not a panacea for health, social and environmental problems, but it is central to solving them all,”

Equality is essential for sustainability. The science is clear — people in more-equal societies are more trusting and more likely to protect the environment than are those in unequal, consumer-driven ones.

With six studies published in the 2010s, French microbiologist Didier Raoult added to his already vast publication record. He and his colleagues conducted a wide range of investigations into infectious diseases and their treatments. They took stool samples from patients on long-term antibiotic treatment, looking for alterations in their gut microbiome. They swabbed the throats of pilgrims leaving France for Mecca, searching for evidence of a bacterium that causes brain abscesses. And they studied samples of heart valves and blood clots from patients with heart inflammation to refine tests for the bacteria that cause the condition.

But in January, the American Society for Microbiology (ASM) journals that published the papers announced they were retracting all six, along with a seventh by Raoult’s colleagues. Aix-Marseille University had investigated the research, which was done at its affiliated Hospital Institute of Marseille Mediterranean Infection (IHU), a research hospital that Raoult led until his retirement in 2021. The investigation found the work had not been reviewed by one of France’s highly regulated national ethical committees. It was therefore in violation of French law and the Declaration of Helsinki, an international ethics document that guides clinical research

Scientists express concern over health impacts, with another study finding particles in arteries

Microplastics have been found in every human placenta tested in a study, leaving the researchers worried about the potential health impacts on developing foetuses. The scientists analysed 62 placental tissue samples and found the most common plastic detected was polyethylene, which is used to make plastic bags and bottles.

A second study revealed microplastics in all 17 human arteries tested and suggested the particles may be linked to clogging of the blood vessels. Microplastics have also recently been discovered in human blood and breast milk, indicating widespread contamination of people’s bodies. The impact on health is as yet unknown but microplastics have been shown to cause damage to human cells in the laboratory. The particles could lodge in tissue and cause inflammation, as air pollution particles do, or chemicals in the plastics could cause harm.

Telehealth abortion has become critical to addressing surges in demand in states where abortion remains legal but evidence on its effectiveness and safety is limited. California Home Abortion by Telehealth (CHAT) is a prospective study that follows pregnant people who obtained medication abortion via telehealth from three virtual clinics operating in 20 states and Washington, DC between April 2021 and January 2022.

There were no differences in effectiveness or safety between synchronous and asynchronous models of care. Telehealth medication abortion is effective, safe and comparable to published rates of in-person medication abortion care. In a prospective study across US states where abortion remains legal, telehealth medication abortion, provided primarily without tests, was effective, safe and comparable to previous findings from large US studies investigating in-person medication abortion care.

To protect their mangrove forests and livelihoods, traditional communities in coastal Brazil set their hopes on small-scale tourism.

Extractive reserves are a common type of protected area in Brazil; they conserve the landscape while allowing communities to continue sustainably harvesting their resources. Around 300 families, known as ribeirinhos—or river people—live in 28 villages inside the reserve; another 2,000 families live nearby. Together, they comanage the area with government agencies and have exclusive rights to harvest crabs and shellfish and carry out small-scale agriculture. Their dependence on the natural abundance binds them intimately to the reserve’s 11,000 hectares of mangroves.

The mangroves, in turn, play an essential role in the larger ecosystem. Those in Cassurubá are part of what some researchers and conservationists refer to as the Abrolhos seascape: a network of coral reefs and mangrove forests that harbors some of the highest-known marine biodiversity in the South Atlantic. The mangroves’ leggy roots trap sediment that otherwise would smother coral reefs, and they absorb nutrients that could disturb the estuary’s delicate chemical balance. The trees’ roots and shoots form a natural net that protects breeding sharks and small fish from larger predators and storms. They also protect against coastal erosion and store large amounts of carbon. Brazil alone hosts around 10 percent of the world’s mangrove forests, which in turn store up to eight percent of global carbon in their tissues and the soils they anchor. Yet as rising seas from climate change submerge some mangroves and others fall to development, stands like those in Cassurubá grow more precious.

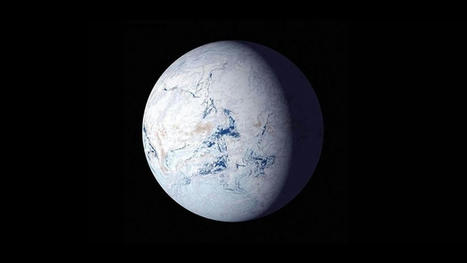

About 700 million years ago, before multicellular animals emerged or plants made their way to land, Earth was plunged into an ice age that lasted for 57 million years.

About 700 million years ago, before multicellular animals emerged or plants made their way to land, Earth was plunged into an ice age that lasted for 57 million years. Now, Australian geologists believe they have figured out what caused Earth to enter its snowball era, when ice covered most continents and oceans. The answer: all-time low levels of volcanic carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Lead author of a study published in Geology, Dr Adriana Dutkiewicz, a sedimentologist at the University of Sydney, says: “Imagine the Earth almost completely frozen over.

That’s just what happened about 700 million years ago; the planet was blanketed in ice from poles to equator and temperatures plunged. “However, just what caused this has been an open question,” she says. “We now think we have cracked the mystery: historically low volcanic carbon dioxide emissions, aided by weathering of a large pile of volcanic rocks in what is now Canada; a process that absorbs atmospheric carbon dioxide.” The extended ice age, also called the Sturtian glaciation, lasted from 717 to 660 million years ago. “Various causes have been proposed for the trigger and the end of this extreme ice age, but the most mysterious aspect is why it lasted for 57 million years – a time span hard for us humans to imagine,” says Dutkiewicz.

|

Features of a scene such as size and clutter can affect the brain’s sense of how much time has passed while observing it.

How the brain processes visual information — and its perception of time — is heavily influenced by what we’re looking at, a study has found. In the experiment, participants perceived the amount of time they had spent looking at an image differently depending on how large, cluttered or memorable the contents of the picture were. They were also more likely to remember images that they thought they had viewed for longer. The findings, published on 22 April in Nature Human Behaviour1, could offer fresh insights into how people experience and keep track of time.

“For over 50 years, we’ve known that objectively longer-presented things on a screen are better remembered,” says study co-author Martin Wiener, a cognitive neuroscientist at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. “This is showing for the first time, a subjectively experienced longer interval is also better remembered.”

Research has shown that humans’ perception of time is intrinsically linked to our senses. “Because we do not have a sensory organ dedicated to encoding time, all sensory organs are in fact conveying temporal information” says Virginie van Wassenhove, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Paris–Saclay in Essonne, France.

Hundreds of genomes shed light on the marriage habits and social norms of the Avar people of central Europe.

NEWS 24 April 2024 DNA from ancient graves reveals the culture of a mysterious nomadic people Hundreds of genomes shed light on the marriage habits and social norms of the Avar people of central Europe. By Michael Eisenstein Twitter Facebook Email Excavation works conducted by the Eötvös Loránd University at the Avar-period (6th-9th century AD) cemetery of Rákóczifalva, Hungary, in 2006. Scientists sampled genomic data from 279 graves at a cemetery in Rákóczifalva, Hungary, where people of the medieval Avar culture were buried.Credit: Institute of Archaeological Sciences, Eötvös Loránd University Múzeum, Budapest, Hungary Most people know about the Huns, if only because of their infamous warrior-ruler Attila.

But the Avars, another nomadic people who subsequently occupied roughly the same region of eastern and central Europe, have remained obscure despite having assembled a sprawling empire that lasted from the late sixth century to the early ninth century. Even archaeologists have struggled to piece together their history and culture, relying on spotty and potentially biased contemporaneous chronicles that, in many cases, were authored by the Avars’ adversaries. A deep dive into 424 genomes collected from hundreds of Avar graves is filling in crucial gaps in this story, revealing a wealth of insights into the Avars’s social structure and culture1. “These people basically didn’t have a voice in history, and we are kind of looking into them this way — through their bodies,” says Zuzana Hofmanová, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig

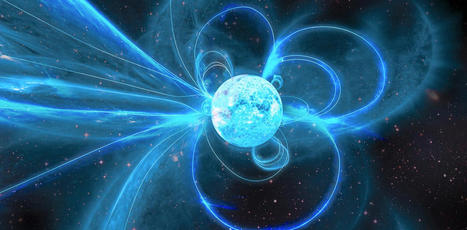

Astronomers caught the bizarre ‘awakening’ of an incredibly rare magnetic star.

After a decade of silence, one of the most powerful magnets in the universe suddenly burst back to life in late 2018. The reawakening of this “magnetar”, a city-sized star named XTE J1810-197 born from a supernova explosion, was an incredibly violent affair. The snapping and untwisting of the tangled magnetic field released enormous amounts of energy as gamma rays, X-rays and radio waves.

By catching magnetar outbursts like this in action, astronomers are beginning to understand what drives their erratic behaviour. We are also finding potential links to enigmatic flashes of radio light seen from distant galaxies known as fast radio bursts. In two new pieces of research published in Nature Astronomy, we used three of the world’s largest radio telescopes to capture a host of never before seen changes in the radio waves emitted by one of these rare objects in unprecedented detail.

The extinction of the dinosaurs sparked an explosion of bird species, according to the largest-ever study of bird genetics.The largest-ever study of bird genomes has produced a remarkably clear picture of the bird family tree. Published in the journal Nature today, our study shows that most of the modern groups of birds first appeared within 5 million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs. Birds are a large part of our lives, a sign of nature even in cities.

They are popular among the general public and well studied by scientists. But placing all of these birds into a family tree has been frustratingly difficult. By analysing the genomes of more than 360 bird species, our study has identified the fundamental relationships among the major groups of living birds.The new family tree overturns some previous ideas about bird relationships, while also revealing some new groupings.

The Nobel Prize-winning psychologist discusses the “noise” that besets human decisions and how institutions can make fairer judgments.

Cognitive psychologist Daniel Kahneman has spent his career studying the ways humans think, including the cognitive shortcuts and biases that shape—and sometimes misshape—our decisions. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 for integrating psychological research on how we make decisions under uncertainty into economics, and he is a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

Kahneman’s 2011 bestseller, Thinking, Fast and Slow, won the National Academies Best Book Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. His most recent book, coauthored with Olivier Sibony and Cass Sunstein and published last year, is Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment. Issues in Science and Technology editor Sara Frueh spoke with Kahneman to get his insights on how we make decisions, the nature of noise and the problems it causes, and whether algorithms could improve decision making.

Bird flu is decimating species already threatened by climate change and habitat loss.

Recent research found that these particular virus subtypes may be able to jump to humans after they were found to be pathogenic in laboratory mice and ferrets. The first person who was confirmed to be infected with H10N5 died in China on January 27 2024, but this patient was also suffering from seasonal flu (H3N2). They had been exposed to live poultry which also tested positive for H10N5.

Species already threatened with extinction are among those which have died due to bird flu in the past three years. The first deaths from the virus in mainland Antarctica have just been confirmed in skuas, highlighting a looming threat to penguin colonies whose eggs and chicks skuas prey on. Humboldt penguins have already been killed by the virus in Chile. A colony of king penguins. Remote penguin colonies are already threatened by climate change.

How can we stem this tsunami of H5N1 and other avian influenzas? Completely overhaul poultry production on a global scale. Make farms self-sufficient in rearing eggs and chicks instead of exporting them internationally. The trend towards megafarms containing over a million birds must be stopped in its tracks. To prevent the worst outcomes for this virus, we must revisit its primary source: the incubator of intensive poultry farms.

As part of a programme to restore arctic fox populations, Norway has been feeding the animals for nearly 20 years, helping boost numbers from as few as 40 in Norway, Finland, and Sweden, to about 550 across Scandinavia

Ranga Dias claimed to have discovered the first room-temperature superconductors, but the work was later retracted. An investigation by Nature’s news team reveals new details about what happened — and how institutions missed red flags.

In 2020, Ranga Dias was an up-and-coming star of the physics world. A researcher at the University of Rochester in New York, Dias achieved widespread recognition for his claim to have discovered the first room-temperature superconductor, a material that conducts electricity without resistance at ambient temperatures. Dias published that finding in a landmark Nature paper.

Nearly two years later, that paper was retracted. But not long after, Dias announced an even bigger result, also published in Nature: another room-temperature superconductor2. Unlike the previous material, the latest one supposedly worked at relatively modest pressures, raising the enticing possibility of applications such as superconducting magnets for medical imaging and powerful computer chips.

People who had tiny plastic particles lodged in a key blood vessel were more likely to experience heart attack, stroke or death during a three-year study.

Now the first data of their kind show a link between these microplastics and human health. A study of more than 200 people undergoing surgery found that nearly 60% had microplastics or even smaller nanoplastics in a main artery1. Those who did were 4.5 times more likely to experience a heart attack, a stroke or death in the approximately 34 months after the surgery than were those whose arteries were plastic-free.

“This is a landmark trial,” says Robert Brook, a physician-scientist at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, who studies the environmental effects on cardiovascular health and was not involved with the study. “This will be the launching pad for further studies across the world to corroborate, extend and delve into the degree of the risk that micro- and nanoplastics pose.”

But Brook, other researchers and the authors themselves caution that this study, published in The New England Journal of Medicine on 6 March, does not show that the tiny pieces caused poor health. Other factors that the researchers did not study, such as socio-economic status, could be driving ill health rather than the plastics themselves, they say.

WELI “Kangaroo Time (Club Edit)”

In our 2024 AAAS/Science Magazine Dance Your Ph.D. Contest submission, we explore kangaroo behaviour through dance and promote diversity. The performance, titled "Kangaroo Time", is based on my Ph.D. field research at Wilsons Promontory National Park, Australia, conducted at the Australian National University in collaboration with the University of Sherbrooke, Canada. My thesis, "Personality, Social Environment, and Maternal-Level Effects: Insights from a Wild Kangaroo Population", is accessible here: https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/248721. I am honoured to have worked under the expert supervision of Prof Loeske Kruuk and Prof Marco Festa-Bianchet.

We delve into animal personality, defined as consistent behaviour that distinguishes individuals, and social plasticity, the extent to which behaviour changes in response to the social environment. We explain how both personality traits and social environment influence kangaroo behaviour, including responses to stimuli like a remote-controlled car, and we demonstrate the role of personality on social dynamics.

The diversity of the dancers, ranging from classical to urban styles, reflects the variations in kangaroo personality, e.g. bolder to shier. These dancers, unchoreographed, improvise their movements, responding to cues and interacting with each other. The dance thus serves as a visual narrative, capturing how kangaroos react based not only on their instincts but also on their social context. This approach demonstrates that kangaroo decisions are a complex interplay of intrinsic tendencies (personality) and social awareness leading to adjustment (plasticity). I hope this performance makes the scientific concepts both accessible and engaging for the audience.

I completed my Ph.D. at the Australian National University, Canberra, in 2021, and worked as a Research Officer. Now, I'm pursuing music, having released my debut EP "Yours Academically, Dr. WELI" and the single "Kangaroo Time (Club Edit)," featured in the video. This project represents a fusion of my scientific work and my foray into performance and creative arts, combining animal behaviour with artistic expression.

Joking draws on complex cognitive abilities: understanding social norms, theory of mind, anticipating others' responses and appreciating the violation of others’ expectations. Playful teasing, which is present in preverbal infants, shares many of these cognitive features. There is some evidence that great apes can tease in structurally similar ways, but no systematic study exists. We developed a coding system to identify playful teasing and applied it to video of zoo-housed great apes. All four species engaged in intentionally provocative behaviour, frequently accompanied by characteristics of play. We found playful teasing to be characterized by attention-getting, one-sidedness, response looking, repetition and elaboration/escalation. It takes place mainly in relaxed contexts, has a wide variety of forms, and differs from play in several ways (e.g. asymmetry, low rates of play signals like the playface and absence of movement-final ‘holds’ characteristic of intentional gestures). As playful teasing is present in all extant great ape genera, it is likely that the cognitive prerequisites for joking evolved in the hominoid lineage at least 13 million years ago.

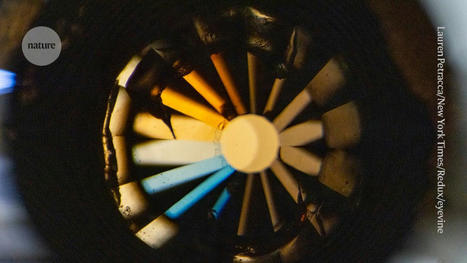

Smokers undergoing counselling to quit smoking are more likely to succeed if nicotine vapes are part of the strategy, according to an international study published in the New England Journal of Medicine this week. As Australia gears up to make vaping prescription-only from March, fierce debate has raged over whether vapes are a menace creating a new generation of nicotine addicts, or a lifesaver for smokers who are trying to quit. The government is hoping the changes to the law will make it much harder for kids to get hold of vapes, while they'll remain available as a cessation aid for adult smokers via their doctors.

The new study suggests vapes may have an important role to play in helping get off the smokes. The researchers recruited 1,246 smokers, 622 of whom received counselling along with free e-cigarettes and e-liquids. The other 624 underwent counselling but were given a voucher to spend on anything they liked, instead of the free e-cigarettes. Six months on, around three in five smokers in the vaping group had stayed off the smokes in the week before their check-up, compared to around two in five among the other group.

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...